Writing this from my comfortable chair in my comfortable home that protects me from the vagaries of the weather outside, it's hard for me to fully understand what the intrepid folks that settled the American West truly went through. Most simply wanted a new place to live and raise a family, but a few went far beyond that. They built something extraordinary that would exist long after they were gone.

This is exactly what an adventurer by the name of

Cabot Yerxa (1883-1965) did. He arrived in the

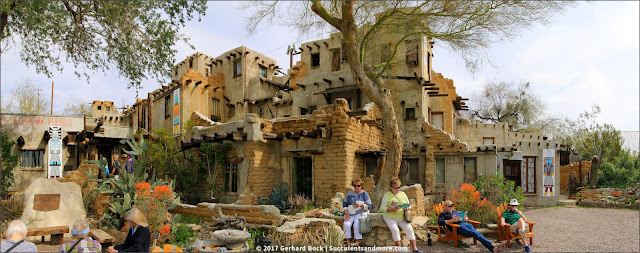

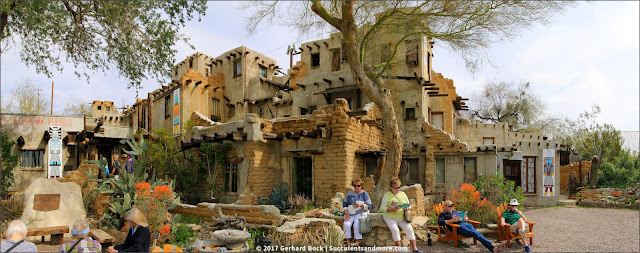

Coachella Valley in 1913 at age 30 years after having lived in Alaska, Cuba and Europe (he even studied art in Paris). He began to homestead 160 acres in the middle of the desert north of Palm Springs and soon discovered two aquifers, one a natural hot spring and the other a cold aquifer that still provides fresh water to the City of Desert Hot Springs. In 1941, at age 57, he began construction of what would become known as Cabot's Old Indian Pueblo Museum:

The Hopi-inspired structure is hand-made, created from reclaimed and found materials Cabot was inspired as a young boy when he first saw a replica of a Southwest Indian pueblo at the Chicago World’s Fair. Much of the material used to build the Pueblo was from abandoned cabins that had housed the men who built the California aqueduct in the 1930’s. Cabot purchased these cabins and deconstructed them to build his Pueblo. The Pueblo is four-stories, 5,000 square feet and includes 35 rooms, 150 windows and 65 doors. Much of the Pueblo is made from adobe-style and sun-dried brick Cabot made himself in the courtyard. Cabot modified his formula and used a cup of cement rather than straw to make his bricks (source: Cabot's Pueblo Museum web site).

Cabot's Old Indian Pueblo Museum opened to the public in 1945. Cabot and his wife Portia operated it as a tourist attraction until his death in 1965. Portia moved back to her native Texas and the structure was abandoned. Several years later, a friend of Cabot's named Cole Eyraud purchased the complex and restored it. After Eyraud's death, the property went to the City of Desert Hot Springs, and today the Pueblo is managed by the Cabot's Museum Foundation. According to

Visit Desert Hot Springs:

[The main building] houses an amazing collection of Native American pottery, arrowheads, turn of the 20th century photographs (including a group shot featuring Cabot Yerxa and Teddy Roosevelt, a close friend of Cabot’s mother), original oil paintings by Yerxa, a sculpture by Chief Semu of the Chumash tribe (a dear friend of Cabot’s), furnishings (like Buffalo Bill Cody’s chair) and more. It also houses his Alaskan collections – artifacts he gathered while living with the Alaskan Inuits. Among his many achievements, he wrote the first Inuit–English dictionary, which is in the Smithsonian Institution.

I visited Cabot's Desert Pueblo on my recent

whirlwind trip to Palm Springs. I think I had a smile on the my face the entire time I was walking around the compound. This is the kind of place that speaks to me with its quirkiness and eccentricity. I only know a little about Cabot Yerxa, mostly from the excellent 30-minute documentary they play at the trading post/gallery (

click here to watch a 4-minute excerpt). It seems to me he was a guy who simply

had to build this structure, much like writers

have to write, painters

have to paint, and gardeners

have to garden. Fortunately, the desert provided him with a limitless canvas.

While not at focus at Cabot's Desert Museum, there is a wealth of desert plants all over the compound, ranging from non-native Euphorbia tirucalli 'Sticks on Fire' to native cactus and shrubs.

|

| Euphorbia tirucalli 'Sticks on Fire' |

|

| Opuntia engelmannii var. linguiformis |

|

| Brittlebush (Encelia farinosa), beautiful even when bare |

Because of our more than generous winter rains, brittlebush (

Encelia farinosa) was going nuts. I had never seen brittle bush as large as this year, and blooming with as much abandon.

|

| The shrub with red flowers is Baja fairy duster (Calliandra californica) |

|

| This Euphorbia tirucalli 'Sticks on Fire' had reached shrub size |

|

| Senita cactus (Pachycereus schottii) on either side of the bench |

As we were leaving, I felt a pang of wistfulness. Is the time really gone when anybody could create whatever their imagination dreamed up? I can't imagine today's regulations would allow a visionary like Cabot Yerxa to build something as fantastical as his Pueblo--not without plans, permits and inspections.

What a quirky cool place! Looks like something out of a movie set. The gardens seemed to have really benefited from the very rainy Spring. Thankfully the pueblo has been saved for all to see.

ReplyDeleteIt does look a bit like a movie set, doesn't it? Mainly because we don't expect something quirky like that to exist in real life.

DeleteAnother interesting stop! But what museum collection does it house?

ReplyDeleteI added an explanation to the body of my post. Cabot Yerxa collected many artifacts during his early travels. His collection of Innuit artifacts from Alaska is particularly noteworthy.

DeleteI expect you're right - a structure could never evolve as this one did under current regulations. Even the tiny, tiny structures created by well-meaning people to give the homeless something better than a tarp or a tent as shelter have been shut down (at least in LA County). I'm glad to see something like this pueblo was somehow able to survive.

ReplyDeleteI suppose in rural areas there's still far less regulation than in cities.

DeleteFrom the era of "roadside attractions" created by the automobile. Winchester Mystery House, that weird tree thing off the 101 in Northern California, etc. The West was not so crowded, and the Sunday Drive was a weekly adventure.

ReplyDeletePerfectly said. I miss the excitement of exploration and discovery. So many people seem to have lost their curiosity and sense of wonder.

Delete